Thriving Shellfisheries in Long Island Sound Depend Upon Our Actions

Thriving Shellfisheries in Long Island Sound Depend Upon Our Actions

September 13, 2019 | By: Christianne Marguerite

© The Nature Conservancy (Lauren Owens Lambert)

The oceans absorb thirty percent of carbon emissions released as carbon dioxide (CO2) from activities such as fossil fuel burning, cement manufacturing, and deforestation. As global carbon emissions continue to escalate, the increasing amount of CO2 absorbed by the oceans is altering the chemistry of seawater, causing its pH levels to drop. The oceans become more acidic, and the acidity deteriorates the exoskeleton of shellfish and corals, putting our marine life and economies at risk. Nutrient pollution further exacerbates ocean acidification. Organizations around Long Island Sound are working to understand and reduce the source of these problems to protect our estuary, our fisheries and our way of life.

Ocean acidification (OA) is a term used to describe the drop in pH that occurs when carbon dioxide gas (CO2) is absorbed by the ocean. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the average pH of our global oceans is about 8.1, which is known as alkaline, or basic. When CO2 from the atmosphere reacts with water (H2O), it forms carbonic acid (H2CO3), which releases hydrogen ions and lowers the pH of seawater. This results in fewer carbonate ions – a mineral that shellfish, corals and many other marine organisms need to grow – available in the water because the released hydrogen ions bind to the carbonate, forming bicarbonate, which is no longer useful to marine life. When shellfish develop, they extract carbonate ions from seawater to produce a protective external shell structure made of calcium carbonate in a process known as biomineralization. Ocean acidification hinders this process, creating a serious problem for the survival of calcifying organisms and puts the entire marine ecosystem at risk.

Ocean acidification also impacts the growth of corals and contributes to the loss of reef structure and the numerous benefits coral reefs provide – from critical habitat for a diverse array of marine life to coastal defense for vulnerable communities. According to Marah Hardt and Carl Safina from the Blue Ocean Institute (now known as The Safina Center), fewer and weaker reefs means “less coastal protection from storms, lost income and food for more [than] one-billion of the Earth’s population dependent on coral reefs for their food supplies, and risks to the $30 billion annual coral reef tourism industry driven mostly by diving.”

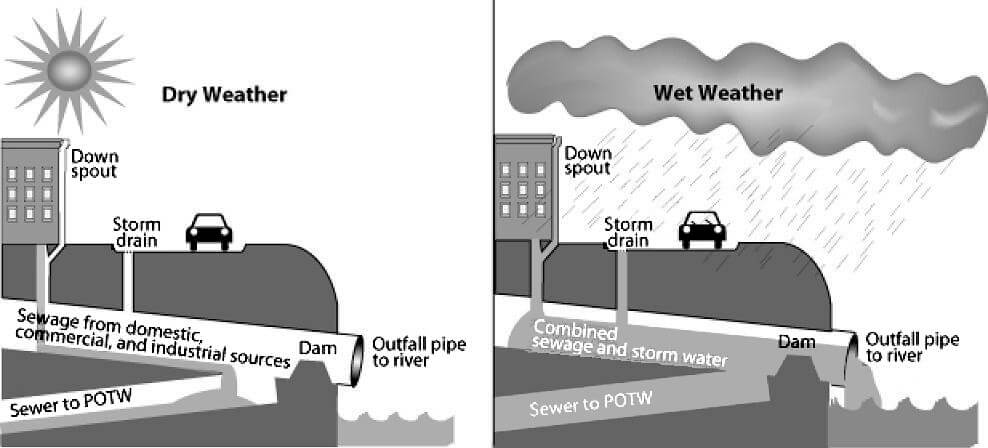

Carbon emissions are the primary source of OA, but they are not the only source. Inland sources also lower pH, exacerbating ocean acidification and the risk it poses to our shellfish populations and the entire food web. Coastal acidification is a serious concern for bodies of water like Long Island Sound where algal blooms caused by nutrient pollution can amplify local OA. Not only does acidic water from runoff and rivers enter the Sound, but excess nitrogen from fertilizers and wastewater treatment systems entering the Sound through runoff, discharge and groundwater seepage increases nitrogen pollution in our coastal waters. Nitrogen pollution leads to the growth of excess algae that releases additional CO2 in the water as it decomposes, compounding the effects of OA. Coupled with rising sea levels and ocean temperatures, the impact of nitrogen pollution exacerbates other pressures on marine life as well as coastal communities that depend on the many benefits the Sound provides.

New York has not seen any wide-spread effects of OA on wild or farmed shellfish populations, though there has been at least one reported case of impact to a local hatchery on Long Island and a pH buffer was added to solve the problem.

“However, with ongoing absorption of atmospheric CO2, incidences of coastal hypoxia, an increased interest and effort in growing the shellfish industry on Long Island, habitat restoration efforts that rely on creation of shellfish beds, and the economic importance of shellfish to New York’s fisheries, there is concern that OA could become more of an issue in our region” says Rebecca Shuford, director at New York Sea Grant (NYSG).

In order to help agencies, businesses, and communities to take a proactive approach to manage the impacts of OA, NYSG has funded several applied research projects in recent years to better understand the mechanisms that can contribute to local acidification in our coastal waters, including the potential effect on shellfish. This research provides information useful to communities and management agencies to get ahead of and implement solutions to reduce impacts on shellfish populations, and the industries and communities that rely on these resources.

In Connecticut (Conn.), there is the same concern. OA reduces survival rates for many organisms, especially juveniles, and shellfish species are particularly vulnerable. According to research published by Nature Climate Change, commercial fishing in Conn. makes up about 70% of all fisheries revenues in the state. This economic dependence on our fisheries, including our shellfish, is at great risk. Beyond reducing CO2 emissions, research published by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), states that Conn. is well positioned to address the problem of local OA. The Nature Conservancy is working with communities on this cause.

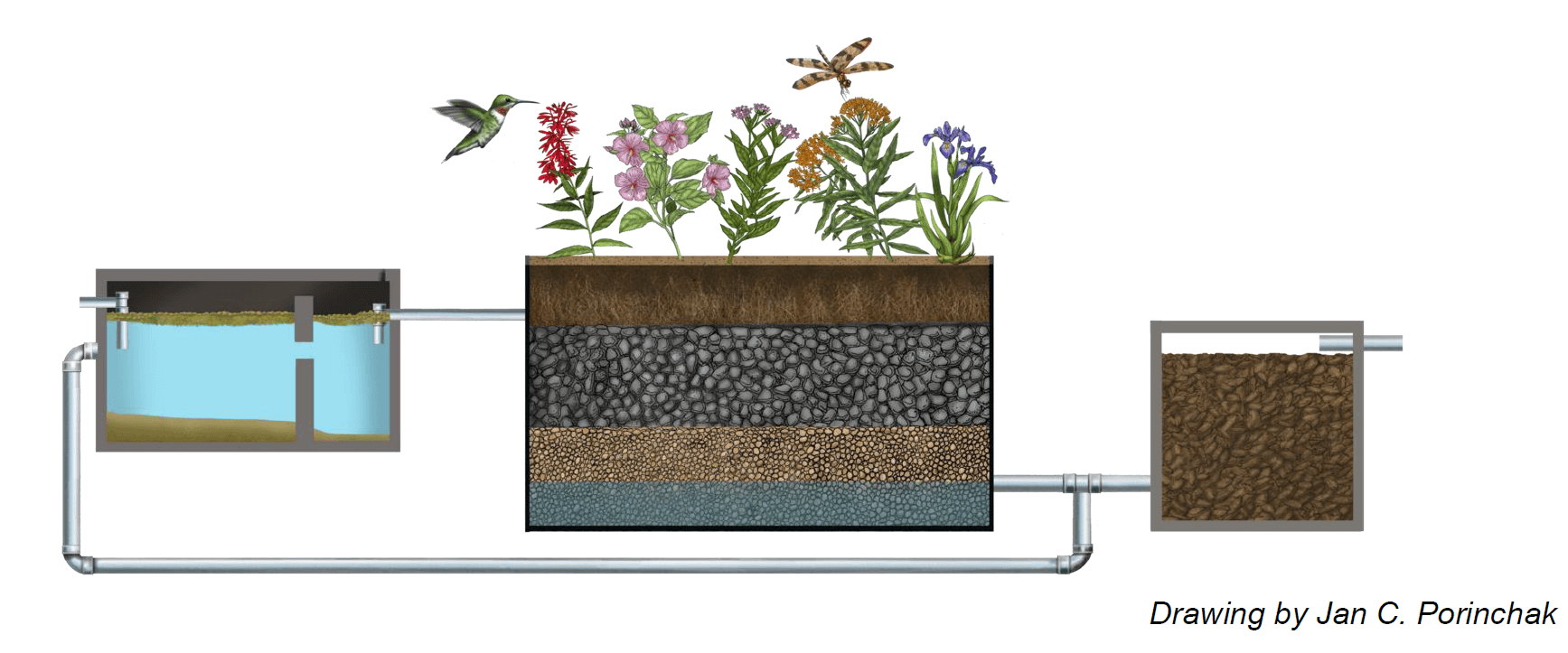

“Coastal communities have an important role to play in reducing the impacts of OA. Reducing nitrogen pollution entering our coastal waters by supporting wastewater treatment system upgrades, reducing fertilizer use, and investing in the protection and restoration of critical habitats such as eelgrass meadows that capture and store carbon and provide critical habitat for marine life, including shellfish, can significantly reduce risk for Long Island Sound” says Chantal Collier, director of the Long Island Sound program at The Nature Conservancy.

In addition to its potential to help buffer the impacts of OA, seagrasses, along with salt marshes (and in the tropics, mangroves) play a critical role in capturing and storing carbon in the ocean. Collectively known as blue carbon, seagrasses absorb two to five times more carbon by area than plants on land can, helping mitigate the impacts of climate change and OA. The Nature Conservancy is working to protect and restore lost seagrass and salt marsh ecosystems to reduce local threats to our marine life and fisheries. While there is still much more to learn about the impacts of OA in the Sound, it is clear that there may be consequences to our shellfish and marine life ecosystems, and that actions can be taken now to prevent such harm.

Learn more about the Northeast Coastal Acidification Network’s Shell Day and The Nature Conservancy’s Shellfish Growers Climate Coalition.